The route

Lai Bab is an overhanging 7a+ (YDS 5.12a) sport route on the Tonsai Beach cliff at the karst limestone peninsula variously known as Tonsai, Railay, Phra Nang, Laem Phra Nang, Krabi or "that place in Thailand". I believe Laem Phra Nang is the accurate name but TripAdvisor and Lonely Planet use Railay, so I will too. Quicker to type, anyway.

|

| Tonsai beach (left) and Railay West beach (right) in 1998 |

|

| Railay East beach in 1998 |

The growth of sport climbing in the 1980s and 1990s, especially at sunny venues in southern Europe, helped redefine the "climbing holiday" from a typically uncomfortable experience, unsuitable for family or less-committed climbers, to something more hedonistic. The final evolution of this concept would be one-stop climbing "resorts" like

JoSiTo in Turkey but an important milestone along that road was the development of sport climbing in genuinely glamourous locations that almost no-one would need persuasion to visit. Railay, with its four white sand beaches, mandatory boat access, jungle backdrop, monkeys and giant surreal rock architecture, was the original, and perhaps still the best, example.

I first became aware of the place in the early-90s, possibly from magazine articles but also possibly from the eccentric 1994 book "Exotic Rock". Though effectively a humble-brag by the author, Sam Lightner, showing off just how extensively he had travelled, it was also quite inspiring.

|

| Exotic Rock's world map. I have still only visited four of these areas. |

The context

In January 1998, Shoko relocated from Tokyo to London to live with me. Before her arrival I had suggested that it might be best if she started rock climbing, as I was unlikely to be giving the sport up. With that in mind, I organised a series of trips to aesthetic overseas climbing venues that I hoped would sell the sport better than grotty British cliffs. Over the next two years we sport climbed in Tenerife, Mallorca, Railay, Smith Rock, Red Rocks, Siurana and Buoux, bouldered in the Seychelles and put up new trad routes on Inishturk island in Ireland. It helped that my career trajectory was in good shape at that time and money not a major constraint. There was no camping or similar hardship involved in any of these trips.

That said, when researching a one week visit to Railay for March 1998 I did have a brief dilemma. The area had a luxury hotel (then part of the

Dusit group, now

The Rayavadee). I guessed Shoko would feel cheated not to stay there but the price was outrageous. We compromised by booking a standard backpacker hotel for the first few nights then the Dusit for the remainder.

This worked out well, though it quickly became obvious that the Dusit was not used to hosting climbers. Right from our arrival we confused them by marching into reception with our bags rather than being dropped off on their boat shuttle from Krabi. Then we raised their eyebrows further by setting off out of their compound with backpacks and a rope to re-join the proletariat and climb.

The accommodation itself was quite fabulous. We had our own two storey villa with a little private plunge pool outside. Phra-nang beach, the prettiest of the four beaches, was a short stroll away on manicured lawns through palm trees.

Whether the Dusit was worth the price I was less sure. We had also enjoyed staying in our OK hotel room with its quasi-functional plumbing and noisy ceiling fan on the previous nights. I have been lucky to stay in quite a few fancy hotels over the years, also flown first class several times and eaten in some famous restaurants (

Le Manoir, four different

Nobu's, etc). These experiences have left me undecided as to the actual value of luxury. I have noticed that there are several ways in it can disappoint. An obvious one is if expectations are set unrealistic high. Then there is the anxiety brought on by the excessive choice which is often a feature of high-end travel;

pillow menus, for example. Arguably, luxury only becomes truly luxurious once it becomes routine, and you are able to, say, sleep all the way through your first class flight and not over-order champagne and fiddle with the movie channels. Overall, I think it is good to sample this kind of thing a few times in your life then convince yourself you don't need it.

|

| Queen Shoko in our private pool at the Dusit |

|

| And slumming it on the backpacker beach |

On that theme, I had a bizarre encounter during our Dusit stay. We were walking back along Phra-nang beach in the early evening after climbing at some cliff at its far end. A european guy in a Dusit uniform yelled at me to ask - not very politely - for help. It turned out that he needed to move the Dusit's wooden shuttle pier higher up on the beach away from the tide line. It was a four person job and he was one short. For some reason, I agreed. It was a brief task - we only had to stumble a few metres - but the pier was brutally heavy and, sans warm-up, felt like a back-strain risk. When the job was done, Shoko and I stepped off the beach into the Dusit's compound. Uniform-guy started yelling again, this time warning that we were on private property. "I know", I replied, waving our room key, "We are guests". His face fell satisfactorily but we didn't hang around to see what he would say next. It dawned on me that he had only targeted me for help because he had assumed from my climber clothes that I couldn't be staying in the hotel.

The next evening we were eating in the Dusit's main dining room when uniform-guy came over to apologise. With hindsight I realise that this would have been an excellent opportunity to fake great outrage and a stiff back, and insist on compensation, or, at least, many free drinks. Instead I made a pious little speech about stereotyping, and suggested he treat climbers with more respect going forward.

The climbing, of course, was pretty good. Diary notes aren't very detailed, but I remember that Shoko had fun and was solid on the routes we tried up to ~6a (YDS 5.10b), including

Massage Secrets, a cool three pitch route with amazing tufa stalactites. This was so good that we did it again on our departure day to get more photos.

|

| Shoko following Massage Secrets |

|

| ... and at one of the belays |

The ascent

We did not venture over to the Tonsai beach cliff until late in our stay. The hike from the Railay West beach passed over an area of low-angle rock which I remember being sharp and awkward. At that time, there was just one beach bar and some very rudimentary huts at Tonsai. In my memory, it is populated by the sort of hairy German stoners who were a fixture at cliffs like Siurana in the 1990s, but that's probably totally inaccurate and unfair. I didn't intend to try anything "hard" but ended up watching someone on Lai Bab and thinking "I could do that". To my surprise, I flashed it. Not an onsight as I had observed the previous climber use a non-obvious undercut which proved to be essential beta. I was reasonably accustomed to flashing routes at that grade but not so often that I wasn't really pleased. It was very cool to climb smoothly on something so steep. The wall was around 45 degrees overhanging.

On the way back to the Dusit we got waylaid at a beach bar, first watching the sunset and then sitting on the sand while hippy firedancers performed to

Leftism - that ubiquitous soundtrack to the mid-90s. A very clichéed experience but great. If someone entrusted me with a time machine to revisit moments from my life, I'd probably set the dial to that day in 1998 first.

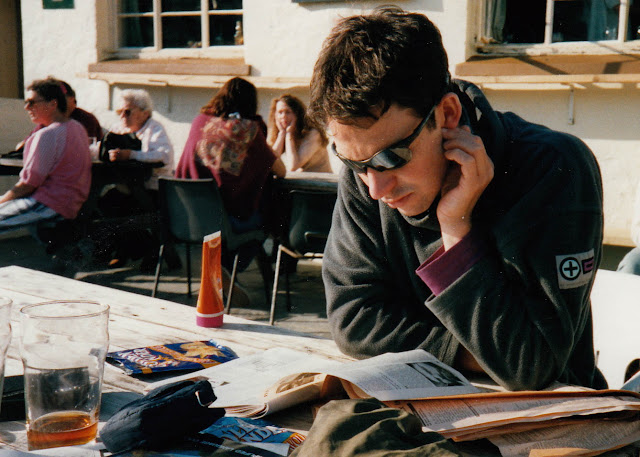

|

| My flash ascent of Lai Bab |

Subsequent ascents

I have not climbed in Thailand subsequently. Shoko, Leo and I did spend about a week in Ao Nang, a few kilometres west of Railay, in January 2007. Though it was a strict "non-climbing" holiday, we did day-trip in a boat over to Railay. One change was immediately evident: the whole Tonsai beach area had been developed. Presumably as a consequence, what had been an empty crescent of white sand and blue sea was full of moored boats and the water had become brackish and unappealing. I made a mental note that the place was now "spoiled". But then I remembered that before we visited in 1998, some friends, who had been there a few years earlier, had warned that the place was too popular and "ruined" - which had not been our experience at all. In the same vein, while researching this blog post, I noticed a commentator on Mountain Project complaining that the place had been "discovered" since his first visit - which had been in 2009! It is all relative.

|

| Leo on Railay West beach in 2007 |